The tree – Acrylic and pastel on board

The young boy’s creative talent was obvious at an early age and upon seeing his art, a teacher at his school near Dorking told him he should definitely “take it up”. The precocious boy interpreted the teacher’s word ‘up’ as an instruction, not simply to pursue a career in art, but a far greater responsibility – to raise the form to another level. From that point onward, he resolved to take art ‘Up’.

That young boy was John Rich and he was my father.

My earliest memories of him were when we lived near High Wycombe, when I would venture up to his studio, with its pungent smell of turpentine and cigarette smoke. I’d watch him delicately apply tiny amounts of oil paint to an old portrait painting, wearing big magnifying glasses on his head and his face almost pressed against the canvas.

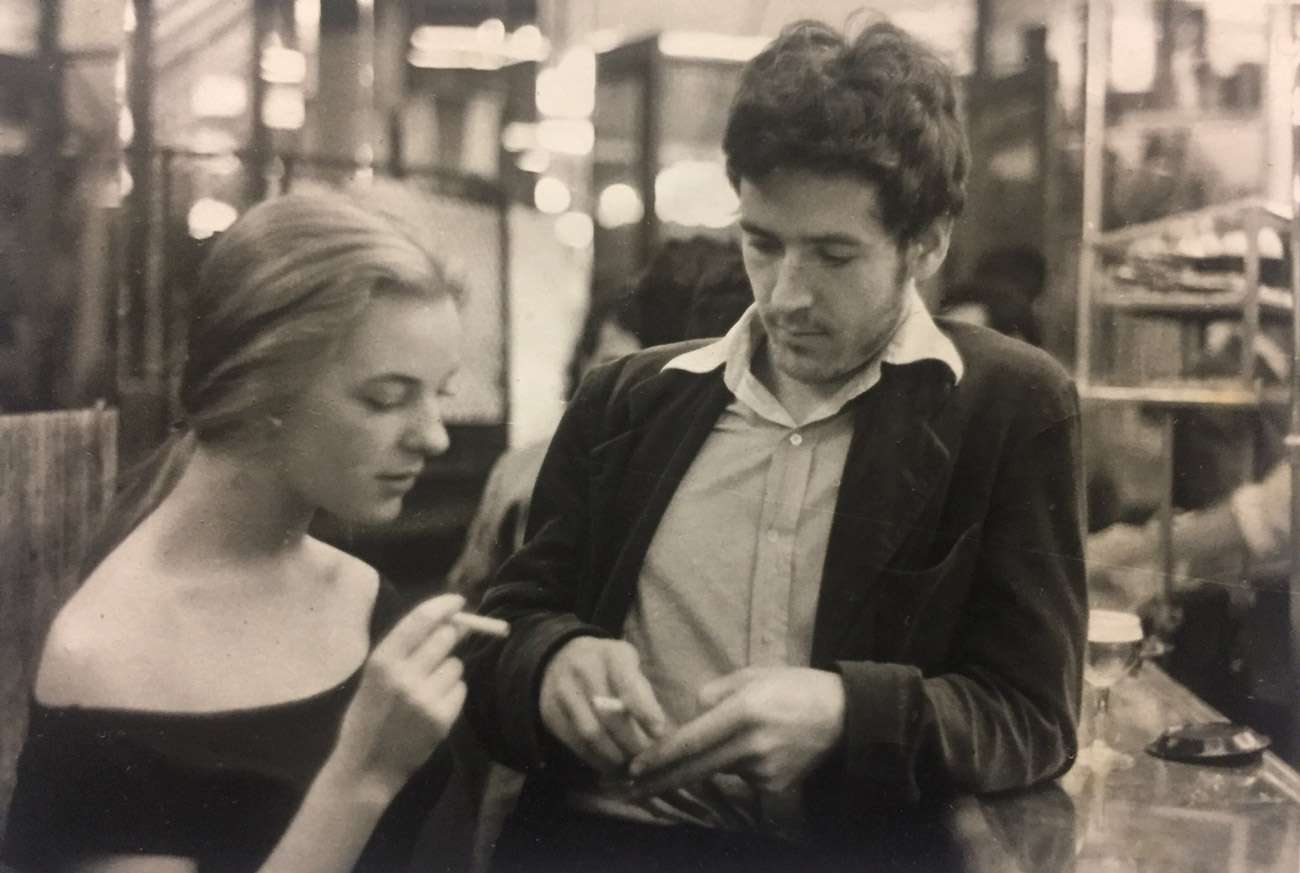

My mother and father in Paris

At this time, when I was a boy, my father was occupied as a self-taught picture restorer. He had ‘retired’ from producing his own art and was doing his best to focus on a growing family with five boys to support. A challenging task for someone so committed to being an artist and struggling with bi-polar. But if I may say so, he appears to have done a decent job, as my brothers and I have turned out largely fine! And how things would have been different if he hadn’t had the support of my loving mother, Elizabeth.

Not that I really knew any of this at the time. I was the youngest son and all I was aware of was this somewhat imposing figure, occasionally the disciplinarian, sometimes fierce or distant, and at other times, the clown or wild storyteller. It was much later that I would discover why he appeared to swing between these very different characters quite so much and learned how my mum inspired much of his work but also enabled him to function, as a father, an artist and almost at whatever else he put his fertile mind to.

It was shortly after John started renting the top-floor flat in a building on Shere Lane in Shere village that they first met. Both were in their teens, and both romantic and artistic. Elizabeth lived in the house opposite and their bedrooms faced each other across the road. I imagine they continued their courtship in mime across the road after spending their days holding hands and walking for miles across the North Downs together.

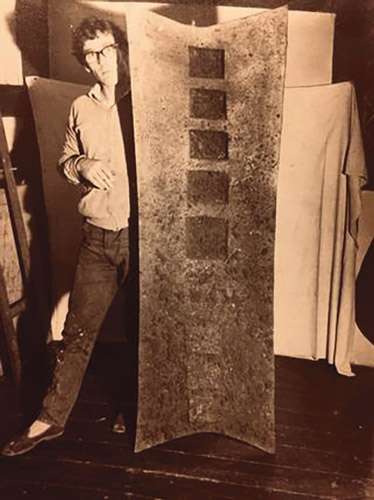

Setting up an exhibition in 1963

He was studying at the Epsom School of Art and then went on to the Slade in London. Then he won a scholarship from the Guildford School of Art to study in Paris, at the Academie Grande Chaumiere and Academie Julien – and so off they went to France. While he studied and painted – and began the journey taking art ‘Up’ as the young John Rich had been instructed – she became his muse and a model, and looked after the practical necessity of making a living.

Upon their return to England, John was primed to make his mark on the London art scene. A contemporary of Peter Blake and David Hockney – exhibiting alongside them – John Rich would go on to have critically successful one-man shows at the Rowan and Grabowski galleries in London. Reviews in the Guardian, New Statesman, Observer and others followed. The Times described him as “an inventive and determined artist with a line of his own.” He became an artist of some standing, exhibiting with the Young Contemporaries and the London Group.

The London Group was originally formed from members of The Camden Town Group and The Vorticists movement. It was a reaction to The Royal Academy’s dominance over the London art world that restricted artists in their ability to choose what they learnt in their classes, made and exhibited. The young original members set out to radicalise the art scene, by giving artists access to affordable exhibition venues, where they could curate their own shows.

At the time John Rich was involved in the group, it flourished and marked a golden era in their bid to revitalise the art world, as they became the group of choice for all new emerging artists, continuing to host affordable and popular shows.

Despite this auspicious start to his career, John and Elizabeth then decided to start a family. With his commitment to art above that of making money, John had no interest in becoming a commercial artist. Making art this way would not support a family and so he resolved to take art up again after this more immediate demand on his time – and make money some other way.

And so, in the course of his restoration career, he cleaned and restored a variety and range of paintings and became regarded as one of the leading picture restorers in the country.

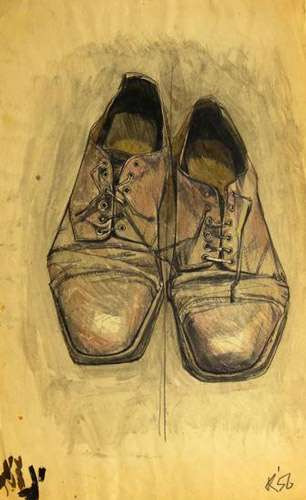

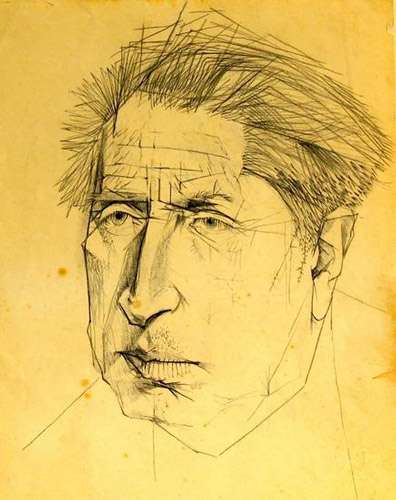

Early pencil sketch

Many moons later, on a chance visit to Shere, the family found The Malt House, the building where John had earlier rented a flat as a teenager, was available for sale. His old landlord was so pleased to see him that he made sure he got the house. My parents became reacquainted with the village and the rest of us settled into these beautiful new surroundings.

By now I was a teenager and my brothers were beginning to leave the nest. Now in his 50s, my dad felt he could ‘retire’. He quit restoration and started to paint again and to write. After so long, an interruption in his practice as an artist had meant falling into obscurity from the contemporary art world. But he felt compelled to begin again and to retrace his steps. He energetically established a studio at the top of the house. He wrote “An artist is both creator and creature of art, a product and producer of its history, the past to which the artist responds and the future for which he or she is responsible.”

In his early years as an artist working in Paris and London, he had shifted his style from Figuration to Abstraction. When he retraced his steps as an artist in later life, he also witnessed something of a revival in figurative painting. “The abstract has apparently run its course and ended in the cul-de-sac of minimalism” he said, and he felt it was time for revision and reassessment.

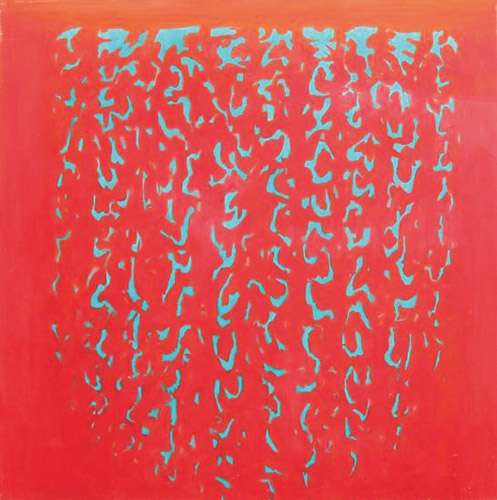

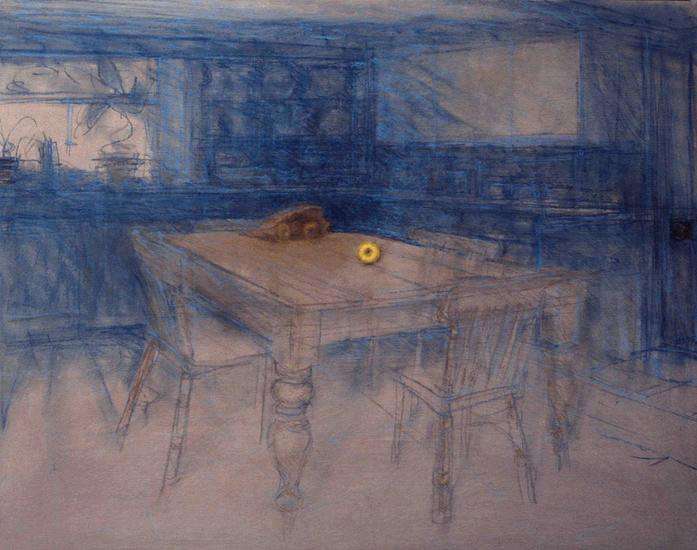

Untitled. INTPR 3113 – Acrylic and pastel on board

Having returned to Surrey, many of the works from this period were inspired by the local flora and fauna of the local area. I would often venture upstairs, as I had done as a youngster, but this time there were no turpentine fumes, he had quit smoking and what I saw on the huge easel was something he had created, not an old work of art that needed repair. He appeared now, to my teenage eyes, to be the old master, doing what he wanted and truly starting to take art ‘Up’.

However, his self-imposed exile whilst affected by bi-polar, encouraged a growing feeling of disillusionment about the contemporary art industry. At this time, its focus was firmly on youth and spectacle. Arts awards such as the Turner Prize, were not open to those aged over 50 and the tumultuous rise of Damien Hirst and the Young British Artists, dominated the headlines. He wrote at the time that “In the Sixties the history of art was taught… as if it began with the Impressionists, in the Eighties as if it began with Andy Warhol and at the turn of the century… as if it began with Damien Hirst.”

His art, informed by aesthetic judgement and expertise gained through intense study of artistic movements and trends, did not appear to fit the fashion of the day and, not for the first time, he questioned his place in the new art world order. He went on to write “The concepts of ‘quality’, ‘better than’ or ‘of a higher or finer order’ – indeed any judgement – is seized upon as evidence of the heresy of elitism, class privilege and snobbery. The punishment for which is exile.”

Early Paris, study 4, – pencil sketch

These were difficult times and his mental condition could make him hard to live with. But then I was a teenager, so no doubt I made things hard for him too! Despite this (or perhaps because of it) John Rich went on to produce a significant body of work, rapidly developing through various styles.

Then the time came when I would leave home and my relationship with him changed again, as it does. I would often return home and make regular trips up to his top floor studio to see the latest creation. Over the decades, the art developed from the figurative, to abstract and finally to sculpture -or ‘wall hung reliefs’ as he called them. Sometimes he would appear to sleep for weeks and nothing would be made and few words shared. We managed to travel a little together and the relationship shifted again to something even better. First to New York and then, sixth months before his death, Morocco.

It took a few more years for me to reflect on his life and to decide how I could in some way reconnect with him and celebrate his creativity. I resolved to make an exhibition of his work – as big as I could. To pull his hundreds of sketches, mock-ups, paintings and reliefs out of storage, out from behind cupboards and out from underneath drawers – to get his work seen, as art should be. To begin to tell the story of my father the artist.

Untitled – Abstract 30

If we are open to them, there are occasional, fleeting moments of insight, comfort or revelatory engagement which strike us, often by surprise, for example in encounters with the natural world. Through his art, John Rich’s work serves both as a record and as a source of these experiences.

John Rich had felt driven to take art ‘Up’ throughout his life and now I felt compelled to put his work ‘Up’ on some walls, for as many others to see as possible. To make a small step toward the artist regaining the recognition that eluded him for many years. So, I persuaded my mother that we make some space for a ‘pop-up’ art gallery in the family home!

Now, the Pop-Up Gallery with Garden celebrates art whilst raising awareness and funds for charity. The current exhibition displays the diverse creative output of the artist, John Rich, who lived and worked in Shere for much of his life. It features over two hundred artworks across three floors.

Early study 2, Dr Conrad Hirsch – pencil sketch

The garden, designed by Elizabeth, is inspired by the old trees that frame the space. She notes that “Nature is extraordinarily resilient and persistent as it seeks out the light. It defies the elements that could crush it and, in its life-affirming way, it can encourage us to feel optimistic. Gardens are meditative, nurturing spaces and this garden aims to present the unexpected to heighten our awareness of difference. It is a celebration of diversity in nature and in human nature.” And so, the garden complements the gallery and aims to reflect the harmonious life-long relationship between the artist and his muse.

The gallery and garden are open at weekends from 12noon to 6pm and at other times by appointment. As it’s run by members of the Rich family and volunteers, it’s best to check the calendar on our website (below) before you travel. We aim to be open as many weekends as possible – and can often open on a weekday for you, with a little notice. The entrance is located on Shere Lane, between the William Bray pub and Surrey Trek & Run.

Hundreds of original works and studies by John Rich can be seen at – www.johnrichartwork.co.uk – and keep informed by following @johnrichartwork on Instagram and Facebook.

Untitled – INTPR311 (Private collection) – Acrylic and pastel on board

John Rich on Beauty

There are objects and events which we call beautiful, particular works of art or of nature that reveal a unity of whole and vitality of parts, which correspond, as a metaphor captures its object, to an ideal condition of mind and body, characterised by an integration and self-regulation of their functions and an excellence in their performance, overseen in a state of tranquillity. This is a state of mind and health to which we all naturally aspire and which we rarely achieve: an occasion of perfect adaptation. In the wake of such occasions, the inner conflict and unease within the personality of the beholder are, for that occasion, resolved. It is an integration, a process of successive occasions, which, well observed, can yield insights and connections, to form a continuous transformative process.

Beauty is not a thing in itself, like a presentation of God in his mercy to brighten up our miserable lives. It is not an inexplicable something tacked on to life to make it worthwhile. Beauty is not ‘there’ as if by some intention or any purpose other than availability as a potential of self-reflection. The beautiful object or event is enveloped in striking unity, and is separated and distinguished from its surroundings. This separation arrests and holds the beholder’s attention, which is an indication of its potential. The event – the meeting of the beautiful with the beholder – is not always immediately pleasurable. There are occasions when it may be fearful and disturbing. It is only when it is seen in the light of its relevance, by reason of its correspondence to the state of mind of the person involved, that it can be called beautiful.

Untitled. Relief 32, Mixed media

This is something more than an ‘isn’t that beautiful’ response to standard pieces in art and nature that are pretty as a postcard. I would not say that these popular pieces are too common and predictable not to warrant close inspection. Who can say how deep and moving they are to their beholders? That the beholder is moved and consumed with pleasure is sufficient reward. But, in my view, this response is a primitive one.

On the occasion of a more significant aesthetic experience, one is arrested by the image before one, which seems to stand out from its neutral surroundings. The body relaxes and the mind is invited to see its reflection. This self-reflection, if the occasion happens to be auspiciously timed, can yield insight and illumination. But, in the normal course of life, it can rarely be repeated or expanded upon. It is contingent on the unique conditions of that occasion. For a more reliable source and aesthetic experience of a higher order, one must turn to art.