The Vanished Workhouse

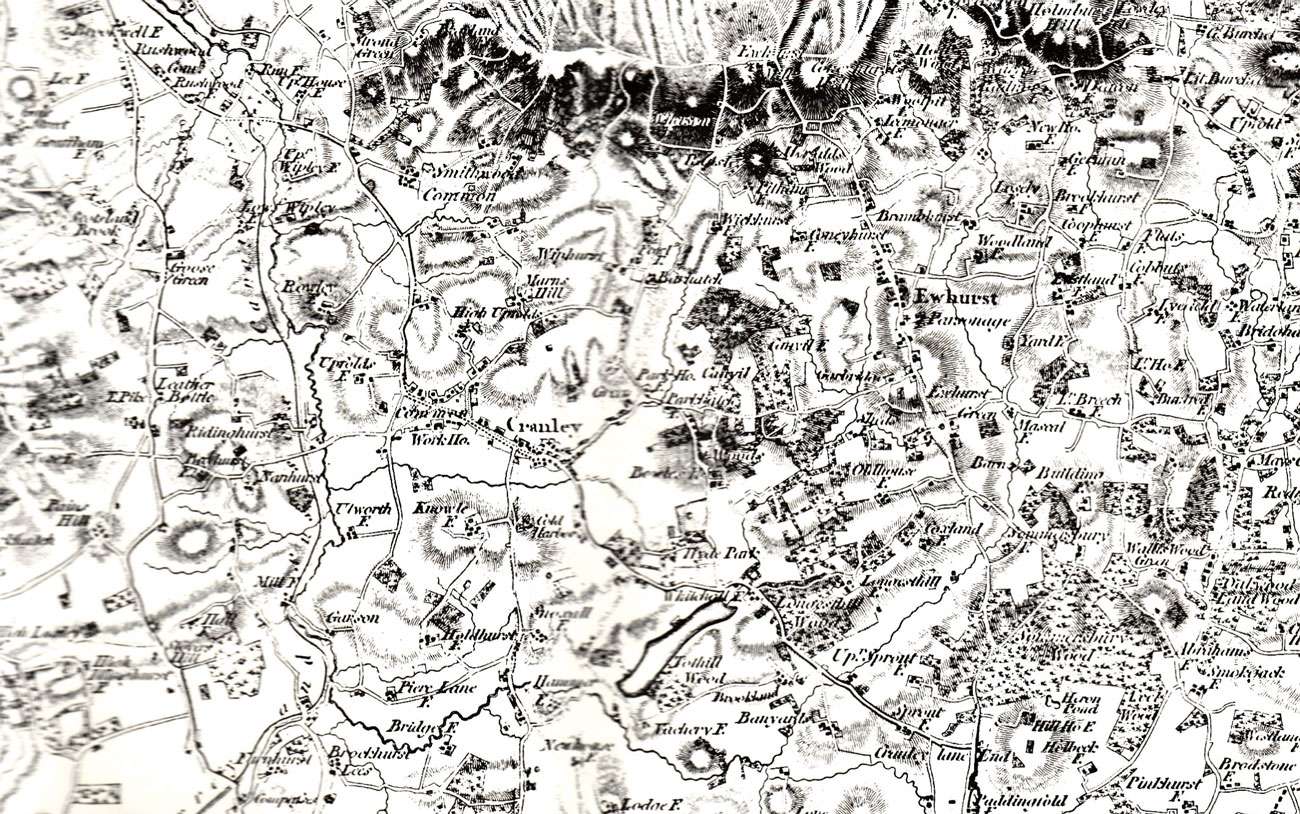

It may come as a surprise to hear that Cranleigh had its own workhouse. There are no known drawings of it, and it was before photography was developed, but it figures on old maps, and quite a lot is known about it and the inmates.

Edward Hassell’s painting of the almshouses in 1830 (Lambeth Archives)

From the time of Queen Elizabeth I, every parish was responsible for its own poor. Every year a ‘poor rate’ was levied on householders and landowners, and two unpaid ‘overseers of the poor’ were chosen to distribute relief to the needy. People who fell into poverty away from their own parish were returned there, in theory. In Cranleigh there were almshouses next to the parish church where poor people could be housed temporarily.

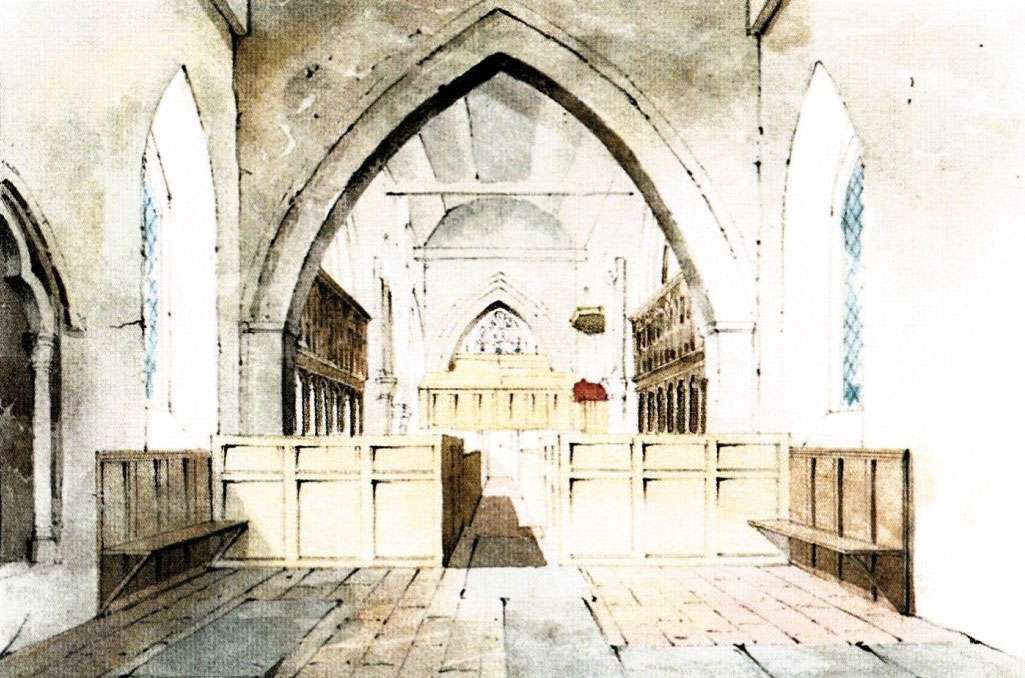

The church interior painted by Edward Hassell in 1828, looking from East to West (Lambeth Archives)

In 1793, the Cranleigh Vestry (forerunner of the parish council) took advantage of a recent Act of Parliament and leased six acres of the Common ‘to be enclosed for the purpose of erecting a poorhouse or workhouse’. The aim was to accommodate 150 unemployed, sick or elderly people (some accounts say 250). The workhouse was three stories high, built of stone. My guess is that, like the Village School (Arts Centre), it was built of local stone, brought down from the Surrey Hills. Adjoining it was a hospital, pest-house (isolation house), a ‘dying room’, two double tenements (houses), stable, barn and other outbuildings. Unfortunately, it was a big mistake to plan on this scale: Cranleigh Vestry expected other local parishes to join in, but only Wonersh did.

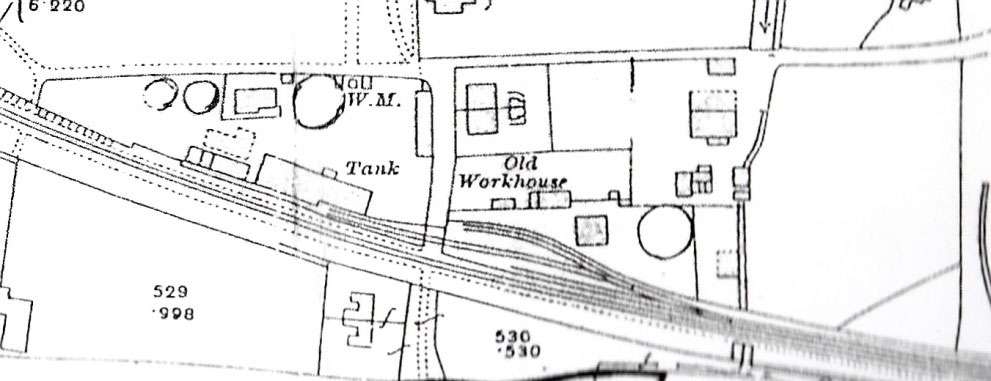

Part of the 1874 Ordnance Survey map, showing the Old Workhouse site next to the railway (now Downs Link Path)

The inmates of the workhouse attended St Nicolas’s church every Sunday, and in 1798 a gallery was erected to accommodate (segregate?) them at the back of the church, across the West window. The artist Edward Hassell painted it, looking from the chancel (altar) end, down the nave. (There are galleries above both of the aisles, too, and these, together with the box pews, make the church seem very ‘closed in’.)

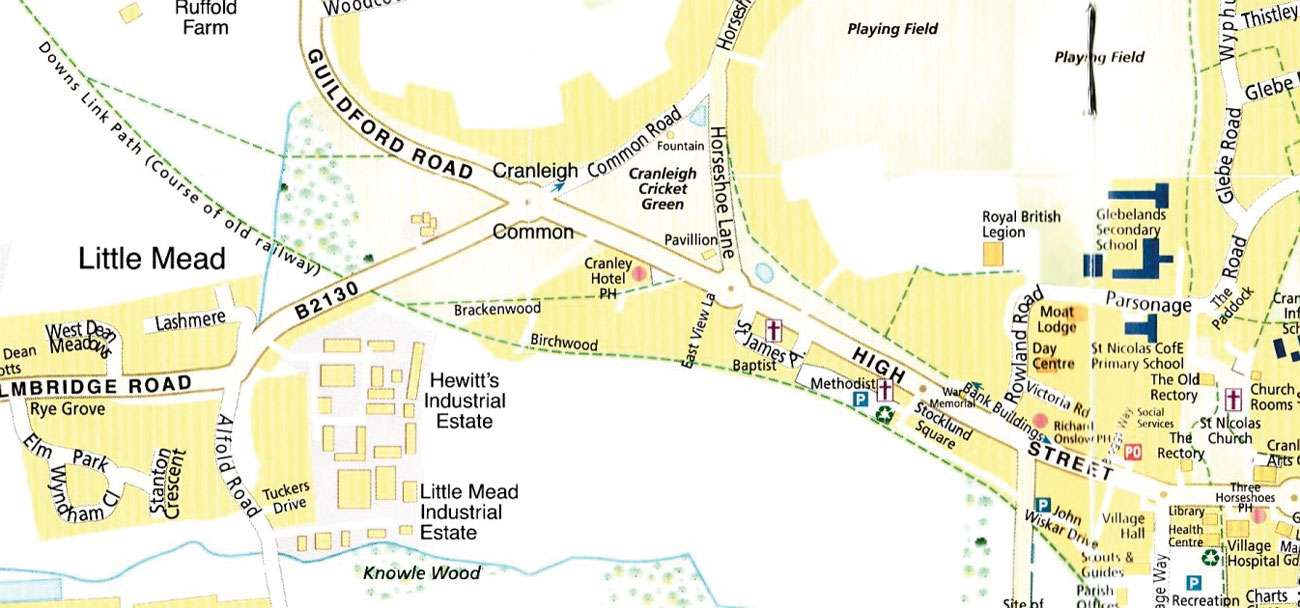

The workhouse site today: Astra House and the rear view of Birchwood

The church interior painted by Edward Hassell in 1828, looking from East to West (Lambeth Archives)

The workhouse was run by a ‘governor’ or ‘master’, and we have records of his buying meat from Parsonage Farm for the inmates – a sheep’s carcase, a sheep’s side, and two hind quarters of lamb. We do not know how it was served up.

Part of the 1915 Ordnance Survey map. A large gasometer has now been built on the site, and a branch railway line brought through it

The number of paupers in the Cranleigh workhouse never approached anything like 150. The highest number was 25. In 1822 there were only 15. In that year, the Cranleigh Vestry resolved to pull down the West wing and in 1825 they decided to demolish the East wing also, deeming the central block as sufficient.

New name for the workhouse site

The Vestry minutes suggest that its members were humane men, trying to do the best for the poor people. George Chitty, a widower blacksmith, found work at Leatherhead and was allowed to leave his two young children to be cared for in the workhouse. A Ewhurst woman was paid 1/- per week to look after a pauper girl, Leah Edwards, and the Vestry negotiated an apprenticeship for ‘Nathan Haynes’s son’ with a local blacksmith, George Steere, paying £5, half of the premium. In 1834, George Elliott, his wife and seven children, and James Toft, his wife and six children were given money to help them emigrate to America.

From the Cranleigh Guide 2018: the old workhouse site can be recognised from its triangular shape by the Downs Link path

Nationally, however, the system was proving too expensive. Towns could not cope with the influx of paupers from the country, and it was impractical to return them to their parishes. So the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed in 1834. This planned to organise poor relief centrally, and the country was divided compulsorily into district-wide Poor Law Unions, serving groups of villages. Cranleigh was put into the Hambledon Union of sixteen nearby parishes. The new union workhouses were built to resemble prisons and deliberately had a régime so draconian that people dreaded going into them and in theory would be motivated to find work in order to stay out.

Cranleigh’s workhouse was now redundant, as the paupers there were moved to Hambledon Union workhouse by 1837. Some buildings remained on the site, which is labelled as ‘Old Workhouse’ on maps for many years. Today the development called Birchwood and the industrial site behind it are built on the workhouse site.

The Cranleigh History Society meets on the second Thursday of each month at 8.00pm in the Band Room. . The next meeting will be on Thursday February 14th, when Jonathan Graham-Brown will speak on ‘The history of theatre in Guildford’.