Violette with her husband Etienne Szabó in London 1940

Violette Szabó was born on 26 June 1921 in Levallois-Perret, Hauts-de-Seine, France, the daughter of Charles and Reine (née Leroy) Bushell. Violette took her father’s British nationality, since Charles Bushell was an Englishman who, as a soldier, had met his wife in France during the First World War.

Some three years after Violette’s birth in France the family returned to England and Charles worked as a driver for his father’s bus company. After only a brief stay, however, the family returned to France and, money and employment being difficult, the children were placed with relatives who could care properly for them. Violette stayed with her aunt in the village of Noyelles-sur-Mer, while her brother was placed with another relative.

Charles Bushell walking with Violette and his wife Reine in Burnley Road London 1924

It was only in 1932 that both children returned to England to join their parents who had left France several years earlier for Mr. Bushell to work as a used car dealer. By this time, two more brothers had been born and the family moved to the Brixton/Stockwell borders in south London.

In 1935 the birth of another son led the family to move to more spacious accommodation in Burnley Road, Stockwell.

Growing up with four brothers made Violette something of a tomboy, but she left school at the age of 14 to work in a French corsetière in South Kensington. She was dismissed when, after a disagreement at home with her father, she ran away to France to see her aunt. When she returned, she worked as a perfume saleswoman in the Bon Marché store in Brixton, a job she held until, after war broke out, she joined the Land Army. After picking strawberries in Fareham for a spell, she returned to Stockwell, determined to do more to support the war effort.

The field, where Lieutenant Fester and his crew dropped Violette by parachute from a USAAF B-24 Liberator on the night of 7/8 June 1944 on her second mission. The spot, at Les Clos, is marked by a memorial stone. Photo courtesy of David Elgy

Her first action was to fall in love with Etienne Szabó, a senior NCO in the Free French Foreign Legion who had first met Violette while visiting London. Violette married him in August 1940 and had only a week’s honeymoon before Etienne was posted overseas. Violette took a temporary job as a Post Office telephonist and waited over a year before Etienne returned to England on leave. Again, they had only a week, but during their brief time together Violette revealed that she wanted to join the women’s forces.

With Etienne’s blessing, she joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), the women’s branch of the British Army. Violette undertook training in anti-aircraft gunnery and was posted in December 1941 as Gunner Szabó, to 481 Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery. After only a few weeks, however, she discovered she was pregnant and, released from the ATS, she found a rented flat in Notting Hill where in June 1942 she gave birth to her daughter, Tania.

Violette playing with her daughter Tania

With a return to the ATS in mind, Violette found a nursing home for Tania in Havant, and waited for Etienne to come home again on leave. But in October 1942, Etienne was wounded, and then killed, in North Africa. When word eventually reached Violette she was working at the Rotax factory in Morden, Surrey. She had taken her daughter from the Havant nursery and had arranged for her to be looked after by a woman in north-west London. When her grief over Etienne’s death turned to a burning desire for revenge, Violette therefore had the opportunity to put herself forward for a more active role in the war.

It is not clear exactly how Violette came into contact with French Section of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), though a note in her SOE file suggests that she was recommended by another agent. French Section lost no time in interviewing her and she was accepted for training and assessment in July 1943. She was posted to Cranleigh and went before the Students’ Assessment Board at STS 7, at Winterfold on the outskirts of the village, in August. The report on her performance and assessment rated her as a D overall (Low, but Pass) and with an intelligence level of a modest 5/10, but summary comments were more positive, noting:

‘A quiet, physically tough, self-willed girl of average intelligence. Out for excitement and adventure, but not entirely frivolous. Has plenty of confidence in herself and gets on well with others. Plucky and persistent in her endeavours. Not easily rattled. In a limited capacity not calling for too much intelligence and responsibility and not too boring she could do a useful job, possibly as courier’.

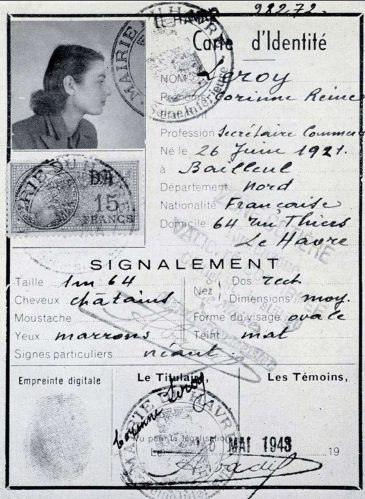

Violette’s French identity card

Winterfold had been requisitioned by the British Government in 1941 and used by SOE as a Special Training School (STS), originally designated STS 4 and later STS 7. It was firstly the training and selection school for the Dutch and Belgian sections of SOE and then the location of the Students’ Assessment Board (SAB) for the French and Free French (RF) Sections. The initial training establishment for French Section had been STS 5 at Wanborough Manor near Guildford, established in February 1941 and continuing until June 1943 when new selection procedures were established at Winterfold, using a small team of psychologists, psychiatrists and military staff to assess and whittle out those not suited to undercover work and begin initial training for those that progressed.

For her paramilitary training Violette was sent to Inverness-shire where she clearly enjoyed the course and the physical exercise, proved to be an excellent shot and was a popular member of her party. But, despite her eagerness to please, her final assessment was that she was ‘temperamentally unsuitable for this work . . . She lacks the ruse, stability and fitness which is required . . . ’

The small Lysander aircraft

Violette had nevertheless ‘set an example to the whole party by her cheerfulness and eagerness to please’. It was also noted that she spoke French and she was permitted to continue to Finishing School training at Beaulieu and then to a parachute training course at RAF Ringway, now Manchester Airport.

Now ready for active service in occupied France, Violette was designated as the courier to Captain Philippe Liewer and his SALESMAN circuit, with Lieutenant Bob Maloubier as arms instructor. Both were Frenchmen and while they waited, through the bad weather of early 1944, to go to France, Violette underwent additional briefing from Leo Marks, of SOE’s codes section.

Pilot Bob Large who landed the Lysander aircraft dodging anti-aircraft fire

Marks realised that Violette was struggling due to the poem she had chosen for her coding and instead he gave her a replacement one that was easier to remember and use. He did not reveal that he had penned it himself in his grief following the death of his girlfriend. Some doubt was later thrown on this story, yet it has become a moving and emotional element of the numerous accounts that have portrayed Violette’s life:

The life that I have

Is all that I have

And the life that I have

Is yours.

The love that I have

Of the life that I have

Is yours and yours and yours.

A sleep I shall have

A rest I shall have

Yet death will be but a pause.

For the peace of my years

In the long green grass

Will be yours and yours and yours.

Violette’s task was to accompany Liewer back to the Rouen and Le Havre areas where he had created SALESMAN on a previous mission. While he and Maloubier had been back in England, however, a wave of arrests had devastated the circuit and Liewer therefore wanted to return as soon as possible to both discover what had gone wrong and to determine whether SALESMAN could be revived.

Violette and Liewer were flown to France in a small Lysander aircraft, landing in a field close to the southern bank of the Loire river, south-east of Tours on the night of 5/6 April 1944. Together, they made their way to Paris from where Violette then went on alone to Rouen by train. On arrival, the news was all bad, Liewer and Maloubier were known to the enemy and were wanted men. Other SOE officers of the circuit and many other local helpers had been arrested. Although much saddened by the devastation of the Salesman circuit and of Rouen itself, she was proud of completing her first mission which she accomplished ALONE for a period of three weeks.

The crematorium building at Ravensbrück where the bodies of Violette, Lilian Rolfe and Denise Bloch were incinerated

She ended that mission, amongst other things, by successfully persuading a resistance group to sabotage the vital Barentin Viaduct in Rouen, part of the major communications route from Germany all the way to Brittany. Remembering that this particular time, April 1944, in the then most dangerous part of France, was just a few weeks before D-Day – one can appreciate the hugely-increased danger.

Returning to Paris to report back to Liewer, Violette managed to fit in two days of sightseeing and shopping in a manner that was typical of the young and vivacious woman that she was. Confirming to Liewer that SALESMAN’s organisation was in ruins, Violette accompanied her leader to a landing ground to the south-west of Châteauroux, where it had been arranged that they would be picked up by another Lysander on the night of 30 April/1 May 1944.

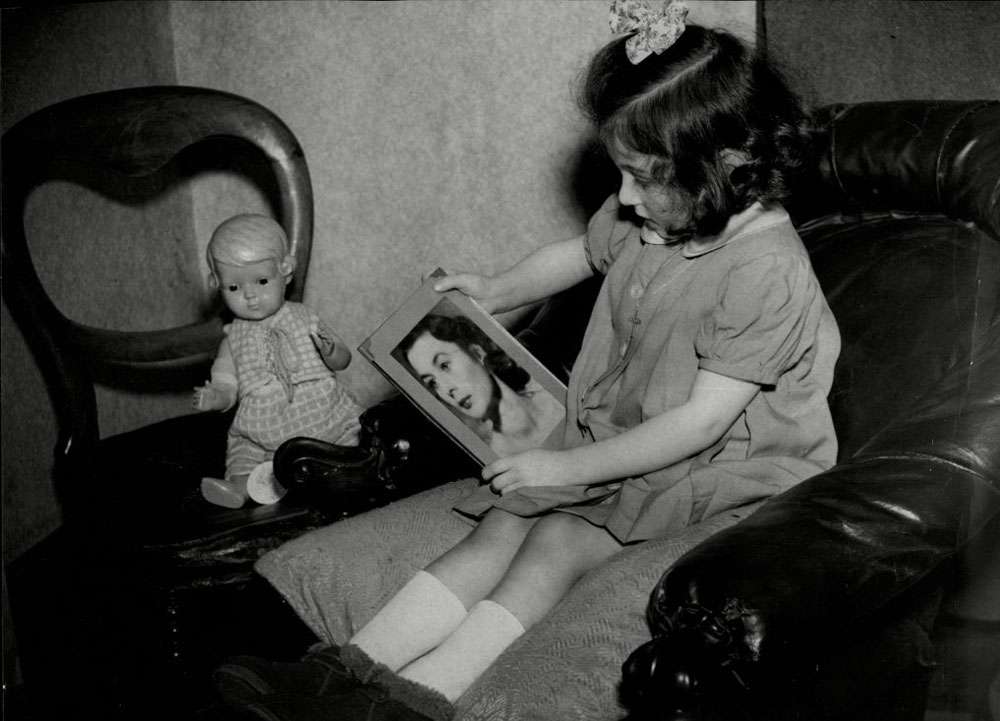

Tania after receiving her mother’s medals from King George VI

The trip proved an eventful one as German anti-aircraft fire, flak, targeted the aircraft, and the pilot, Bob Large, found he could not concentrate properly on dodging the flak while shrieks came from Violette in the rear. He therefore switched the intercom off, but forgot to switch it back on after the danger had passed. Violette consequently remained uninformed of progress and when the Lysander ground-looped (due to a burst tyre from a near-miss by flak) on landing back in England, she was under the impression that they had had to put down, still in enemy-occupied territory. Large went to help his passenger, only to be greeted with a torrent of abuse – Violette believed him to be a German.

After enjoying some leave, Violette reported again for duty. She belatedly received the rank of Ensign in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), designed to side-step the rule that women in the armed forces should not serve in, or indeed behind, the front line. As the FANY were not formally part of the armed forces, observance of the regulation remained intact, while offering the agent some form of quasi-military status, should they be captured. She received orders to again join Liewer in a new SALESMAN 2 circuit in the Haute Vienne region of central France. Bob Maloubier remained in the team, along with radio operator Jean-Claude Guiet, a young American agent, seconded to French Section. All four were dropped by parachute on the night of 7/8 June by a B-24 Liberator of the USAAF, south-east of Limoges.

Tania at home after the death of her mother © Rex Features 1947

Two days after her arrival, Violette was charged by Liewer with making a trip of some 150 kilometres to set up a meeting with another French Section agent. Given that this was a long journey, Violette was offered a lift with her bicycle for the first part of the journey in a car driven by Jacques Dufour, a locally-recruited member of the circuit. Liewer’s later report confirms that Violette took with her a Sten gun and ammunition for the car journey, despite the fact that this would compromise her if stopped by the enemy. Together with another Resistance fighter, Jean Barriaud, Violette and Dufour were approaching the village of Salon-la-Tour when they were confronted by a road block manned by three German soldiers who waved them to halt. Dufour and Violette threw themselves from the front seats onto the road and opened fire while Barriaud, unarmed, leapt from the back door and ran off.

In the face of accurate returned fire from the Germans, Dufour gave the order to retreat through a wheat field, aiming for the cover of some woods about 400 metres away. He and Violette gave each other covering fire in turns while they fell back, but luck was not with them as German reinforcements quickly arrived. They were still some distance from the edge of the woods when Violette, exhausted and with her bare legs covered in scratches and her clothes torn, told Dufour she could go no further, but would cover him while he reached the copse. Reluctantly he agreed and made good his escape through the woods and then by hiding under a haystack in a farmyard. Some thirty minutes after he went to ground, he heard Violette, having been captured, brought to the farm and questioned about his whereabouts. She laughed and answered that he was far away by now.

The local French school, Noyelles sur-Mur attended by Violette

After her capture, Violette was taken to Gestapo headquarters in Limoges for initial questioning and then transferred to Limoges prison. News of her capture was given by Barriaud who, having made good his own escape, had walked 15 miles to alert Liewer. He confirmed that the exchange of fire had lasted over half an hour and asked if the Maquis might mount a rescue attempt for Violette. But before a plan could be worked up, Violette was taken from Limoges to Paris where she was interrogated at the German Secret Police headquarters in the avenue Foch and later moved to Fresnes prison.

On or around 8 August 1944, Violette was among a group of seven young women taken to the Gare de l’Est for deportation by train to Germany. Two other French Section agents were with Violette in the group – Lilian Rolfe and Denise Bloch. They travelled as far as Sarrebrücken in the same train as a large group of male SOE agents being similarly deported and Violette brought great credit to herself when, during an air attack on the train, she and another young woman took the opportunity to crawl along the train’s corridor and deliver much-needed water to the men. The senior officer of the male agents, who was to survive incarceration and a death sentence at Buchenwald concentration camp, made sure that he recorded Violette’s action when he returned to England.

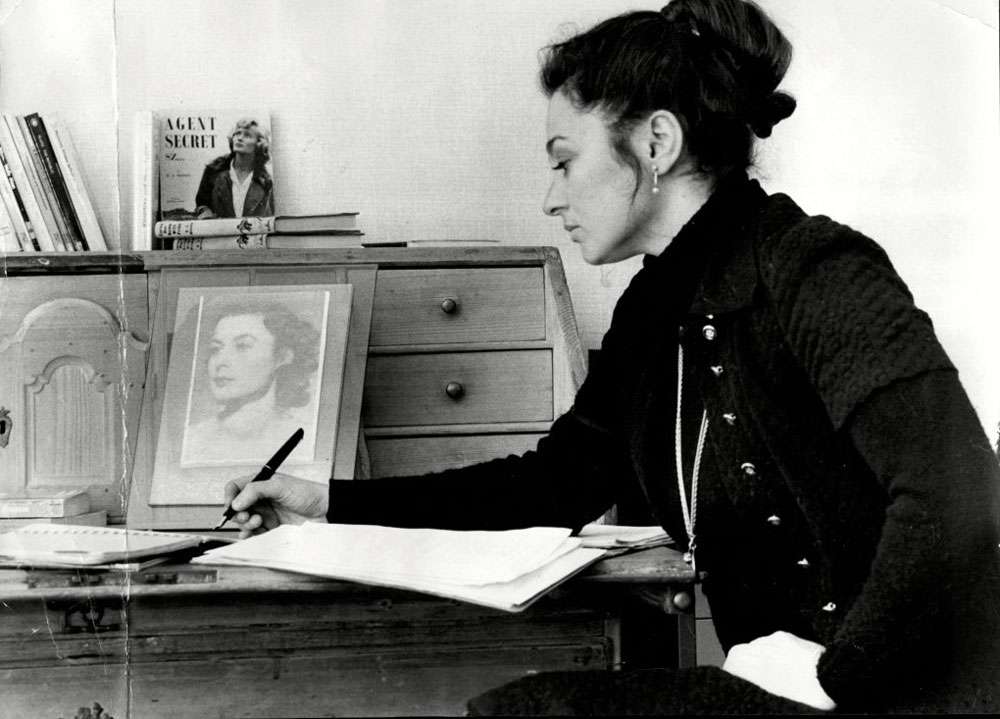

Tania all grown up, reflecting on her mother’s life © Rex Features

From Sarrebrücken the women agents were sent on to the women’s concentration camp at Ravensbrück, which they reached on 22 August 1944. At Ravensbrück, Violette was described as cheerful and determined to escape, but on 3 September, still with Denise and Lillian Rolfe, she was sent to work in a factory at Torgau. While there, she managed to acquire a key to one of the camp gates, but the Germans heard of the key and Violette had to drop the matter. The three agents returned to Ravensbrück in October 1944, but Violette, Denise and Lillian left again on the 19th with another work party, sent to Königsberg where they were made to undertake hard physical labour in the forests and to help build an aerodrome. A Frenchwoman who knew her there, described Violette as still being clothed only in a light short-sleeved summer dress.

On or about 21 January 1945, the French Section girls were recalled to Ravensbrück where, ominously, they were first held in the punishment block which meant they were unable to make contact with their friends in the main body of the camp. Violette was described as still being in the best spirits and physical condition, though all three young women were in a poor state after several months of hard labour and little food. Three or four days later they were moved again to the ‘zellenbau’, ‘bunker’, a segregated block of solitary confinement cells that could not be seen from within the camp.

Violette, as a young teenager

Violette was never seen again by the camp’s inmates and her fate was only discovered during investigations in 1945 and 1946 into the fates of SOE agents. During his interrogation, Ravensbrück’s second-in-command, SS-Oberstürmfuhrer Johann Schwarzhüber, stated that Violette and her two companions were recalled from Konigsberg following receipt from Berlin of an order for their execution. One evening (believed to be between 25 January and 5 February 1945) they were brought out of the bunker and into the courtyard adjacent to it and the crematorium. Reports suggest that Violette alone was well-enough to walk unaided. The execution order from Berlin was read out by camp commandant SS-Sturmbannführer Fritz Sühren, before an SS sergeant named Schult (or Schulter), shot each girl, brought forward singly, through the back of the neck using a pistol. The camp’s doctor certified death and the bodies were immediately taken into the crematorium and burned. Violette was 23 years old when executed.

Both Sühren and Schwartzhüber were caught, tried and executed for their crimes at Ravensbrück, albeit without specific mention of the murders of Violette and her fellow French Section agents.

Violette’s war medals

Violette is the most memorialised of the French Sections agents who gave their lives. She is officially commemorated on the Brookwood Memorial to the Missing 1939-1945, near Woking. Other commemorations abound, though not always accurately. The naming of Szabó Crescent in the village of Normandy, near Guildford, was in the belief that it was at nearby Wanborough Manor that Violette had been among the many French Section agents trained and assessed there. In reality, Violette went to Winterfold, rather than Wanborough Manor.

There is a modest museum in the house in Wormelow, Herefordshire where Violette spent some of her holidays with relatives and in London a bust of Violette graces the SOE memorial unveiled in 2009 on the Albert Embankment, opposite the Houses of Parliament. A blue plaque marks the former Bushell family home in Burnley Road, Stockwell and a colourful mural nearby depicts her life.

The local authority, Lambeth, have a plaque in their Town Hall in Brixton and in Stockwell the Council named a social housing block ‘Violette Szabó House’. Her name is also listed on the FANY memorial outside St. Paul’s Church in Knightsbridge.

In France, the school that Violette attended in Noyelles-sur-Mer (80) is named in her memory and stands in a street now re-named rue Violette Szabó. She is listed at the French Section Memorial at Valençay and a granite memorial marks the spot where Violette parachuted from a USAAF B-24 Liberator on the night of 7/8 June 1944.

A street named after Violette

At the site of the former Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany, Violette is one of the four French Section agents commemorated on a plaque. The zellenbau block, execution yard and crematorium remain and are open to visitors.

Thanks to the 1956 book ‘Carve Her Name With Pride’ and the subsequent film of the same title, Violette became one of the best-known of French Section’s agents. The book, and therefore the film, sometimes strayed from the facts, but with the release of SOE personnel files, Susan Ottaway’s biography of Violette ‘The Life That I Have’ is recommended for a much more detailed and accurate portrayal of Violette’s life. Violette’s daughter, Tania, wrote her own highly-readable account of her mother’s life ‘Young, Brave and Beautiful’, published in 2007.

Violette was originally recommended for a (civil order) MBE as early as June 1945, but this was amended in July 1946 to a recommendation for a posthumous George Cross, ranking alongside the Victoria Cross as Britain’s highest award for bravery. This was confirmed in 1946 and was one of only three such decorations given to French Section’s young women, the others being Odette Sansom and Noor Inayat Khan. Violette was also awarded the Médaille de la Résistance and the Croix de Guerre by the French.

Special thanks to Tania Szabó for the use of family photos.

For further information contact: Paul McCue – Trustee

E-mail: